INTERVIEW

What inspired you to write this book?

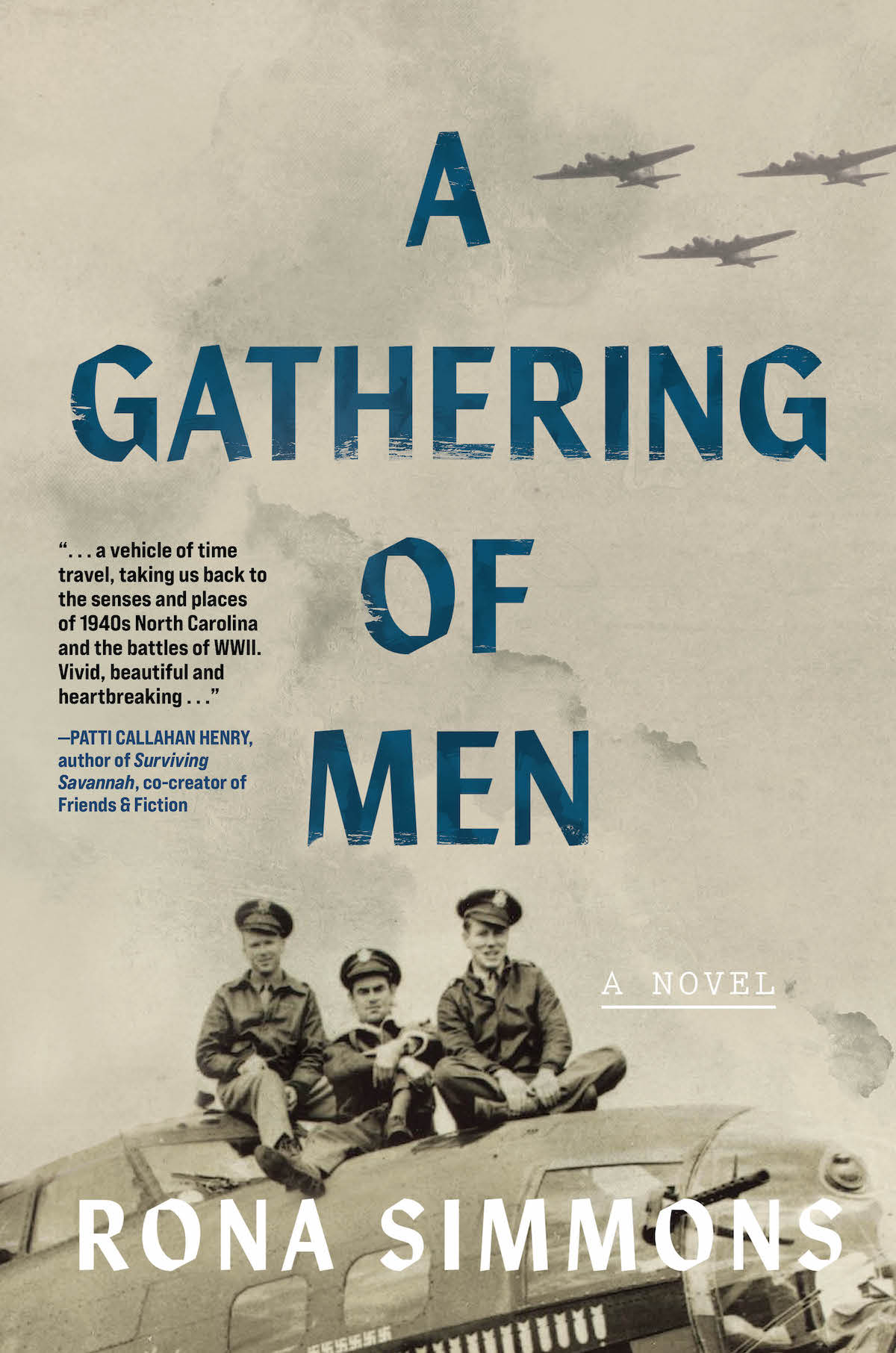

Looking back, I’d say it came about as a result of a confluence of factors. From the research and interviews I did for my prior work, The Other Veterans of World War II, I learned a large percentage of the young men who flooded the recruitment centers had their hearts set on becoming pilots. Yet, an equally large percentage were denied the chance to fly.

As it so happens both my father and my husband’s father became pilots, mine a fighter pilot, and his a bomber pilot. But where I had the luxury of being able to talk with my father about the war and his experiences, my husband lost his father in the 1960s and any chance of hearing his story firsthand.

In the mid-1990s, we began searching for more information about him. We wrote to the government records office and scoured the internet only to confirm what we already knew—that in 1944, a mere four months after arriving in Europe, and after completing only 21 of his assigned missions, Lieutenant Bethea returned to the States. Eventually, however, we connected with a handful of his crew. Although each spoke highly of the young man they once knew, they were reticent to tell us more—which only deepened our interest.

Can you share something about the process of writing the book? There’s no doubt it involved much research.

Yes, it did. Thankfully, I am a natural born researcher, if there is such a thing. I’ve always had a knack for taking things apart, examining their contents and then putting them back together. Research is a lot like that. You start with the topic itself, break it down into manageable pieces, and then inspect each from as many angles as you can devise.

But, I was lucky too, so much more information is available on the Internet today than back in the 1990s. Although the sheer amount of information on a popular topic like World War II was at times daunting, it made my work much easier. I spent hours and hours, well, quite frankly months perusing World War II, Eighth Air Force, and the 100th Bomb Group’s sites. And I connected with Leonard Aubert, the nephew of my father-in-law’s copilot, Lt. Leonard Coleman. Although Coleman was deceased, Aubert had his uncle’s diary from the war.

The diary and the exhaustive research provided much more than a simple chronology of missions and names of the airmen, it helped me weave little details into the story that produce what I believe is a far better more and more compelling work. I’ll give you an example. As the American bombing missions took during daylight hours, returning late in the afternoon or early evening, the mechanics could not begin maintenance and repairs until nightfall, often working through the night. That work took place in the open air at times in the rain and freezing temperatures; and many fashioned small shacks from discarded crates and set them beside their aircraft so they could catch a few minutes rest rather than take the time to walk or bike to and from their barracks.

What were some of the most interesting or surprising things you discovered in writing the book.

For one, I’d say it was realizing how many young men yearned to be pilots. Of course, when the war broke out, flying was in its infancy and carried an aura of glamour with a hint of danger, and a few dollars a month more in their pockets. Further, as my father once explained using today’s terminology, those silver wings were “chick magnets.” So that was another reason to sign up for the air corps.

I’ve heard you mention the term Legacy Generation. What do you mean by that?

Twenty years ago, Tom Brokaw coined the term “The Greatest Generation” to characterize World War II veterans including the dozens he interviewed for his book of the same name. I cannot imagine his readers coming away with anything but a sense of deep gratitude to these men and women and the enormity of debt that we owe all veterans who served during the War.

They are fast disappearing now, with most survivors in their nineties. Thankfully a number of organizations are making it possible for veterans to record and thus preserve their firsthand experiences. These include libraries, universities, and museums across the country, some of whom work under the auspices of the Library of Congress.

But the onus to not only capture these stories but see that they are told again and again falls on the descendants of the veterans, the members of my generation and those to come. We’re not just baby boomers or millennials, we are the Legacy Generation. Keeping alive the stories of what the WWII veterans accomplished is how we fulfill our debt.

And what do you hope people come away with after reading A Gathering of Men?

I hope readers gain a better understanding about World War II and what drove sixteen million people to serve their country, and to understand that not everyone handled the controls of a fighter plane, looked through the B17 bombardier’s scope, or took cover in a foxhole, but that all played a role in winning the war. All are worthy of our respect and honor.